PRESS RELEASE

POP!

Feb 16 – Apr 2, 2023

DIEHL GALLERY

presents

POP!

02.16.23 - 04.02.23

Opening Reception:

Saturday, February 18th • 5–8 pm

155 West Broadway, Jackson Hole

This group exhibition features new work by four gallery artists: Robert Mars, Ray Phillips, David Pirrie, and Douglas Schneider. While each artist has a unique style, they all draw from the long lineage of Pop Art in America. There is a thread of nostalgia that ties these works together, an immortalization and apotheosis of celebrities, objects, and images from a bygone era.

ROBERT MARS

Robert Mars’ new body of work focuses on iconic movie stars from old Westerns, a theme that he has explored for many years. More recently, he has begun to use historical American quilting patterns as the backdrops for his figures. “With these current works I am using a more traditional palette of reds, variations of blues, and off whites to play off of the American flag colors.” This duality of celebrity and traditional craft creates a dynamism to his work that speaks to American heritage in a distinct and multi-faceted fashion.

RAY PHILLIPS

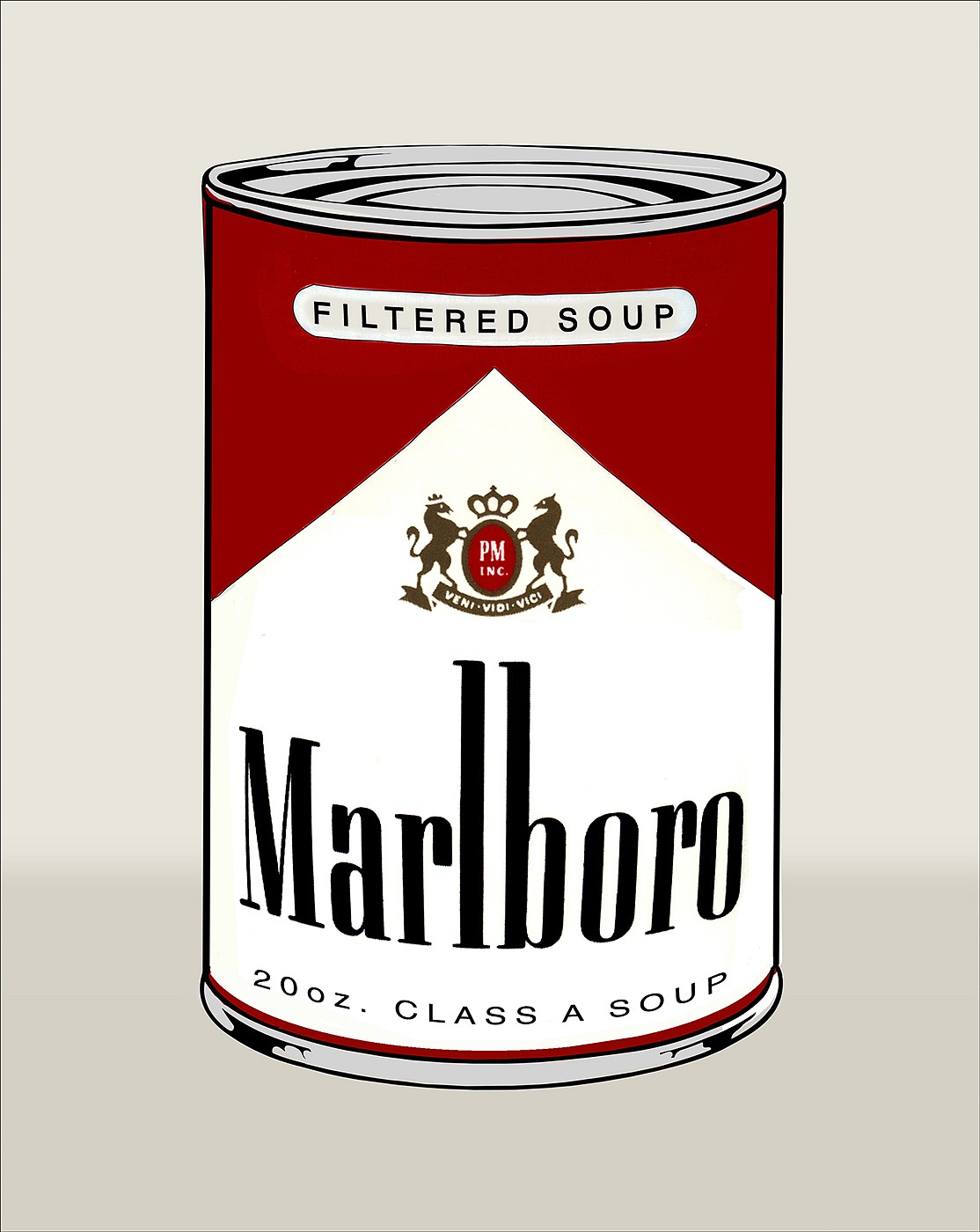

Ray Phillips’ work is deeply embedded in both personal and collective nostalgia. He often draws from his own childhood memories to create pieces that speak to a universal sentiment and a specific cultural age that resonates with many.

Funnypages is a wonderful example of how Phillips’ personal experiences inspire his work. He writes:

For me, my comic books were a big deal. This was prior to the internet and cable TV, and although I was never an avid collector, I enjoyed getting lost in the fantasy and humor of the “Funny Papers”. Even the word “Funny Papers” is silly and old school.

Humor is a perpetual theme in Phillips’ work. Often cheeky and at times, almost irreverent, his pieces are intended to be joyful and sometimes downright comical.

DAVID PIRRIE

David Pirrie has a different approach to the concept of celebrity, and like Phillips, his work is informed by personal experience more so than a collective sense of culture and place. Instead of using familiar characters or objects, he has created his own iconography of the mountains. Pirrie began climbing at a young age, and his reverence for the peaks he paints comes from a place that is not only an artistic pursuit but reflects his passions outside of the studio. “Recent ski mountaineering expeditions into the Grand Tetons, for example, give an intimate sense for the mountain range and its characteristics, which forges a relationship between the images I create and my experience.” Pirrie’s work depends heavily on color theory. He writes:

This aspect of my work is both conceptually and formally driven. Formal in the sense that it is derived from color theory and employed to affect the overall composition, meaning that the color becomes an integral part of the painting. Conceptually, the dots and grids may represent coordinate plotting, metaphorically pointing to the impermanence of man-made symbols that attempt to prescribe location at the intersection of human and geological time.

In removing the individual mountain from the surrounding range I decontextualize the subject, making it symbolic rather than representational. I treat the mountains like celebrities, fashioning larger than life, unattainable, beautiful and mysterious portrayals. I also record their rugged features in detail, as they individually assume their own unique personalities. My use of bright monochromatic colors and dot overlay draws aesthetic and conceptual comparisons to Pop Art, implicating these colossal stone figures in the pop culture lexicon. In this light the work becomes an exercise in re-framing how we perceive the mountains; examining the function of representation and how preserving something in imagery can make it iconic.

DOUGLAS SCHNEIDER

At first glance, Douglas Schneider’s depiction of Audrey Hepburn appears whimsical, with its vibrant palette and snippets from vintage magazines and ads depicting iconic America logos such as Big Boy and Coca Cola. But there is a darker side to Hepburn’s fame that many are unaware of. Known for being slight of frame and delicate, almost childlike, her figure was a visual remnant of being starved as a child during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in WW II. Men and women alike fawned over her distinctive beauty, but the actress herself struggled with a constant internal battle between being an icon of style and a woman plagued by health issues and ailments. Perhaps this is why she was so captivating on the screen; she infused her characters with her own, very real physical pain.

In Schneider’s piece, he seems to capture this duality. The clamoring of the American people for celebrity, almost dehumanizing stars by putting them on a pedestal of fame. The image of Hepburn is lovely; she is surrounded on one side by what resembles vintage wallpaper. On the other, the imagery of the masses, as if these two elements existed inside the actress; one, her internal life and the struggle to find a place of home amid the glamour and the other, the face she presented to the public.